The Eight Faces of Change (and Why They Confuse Us)

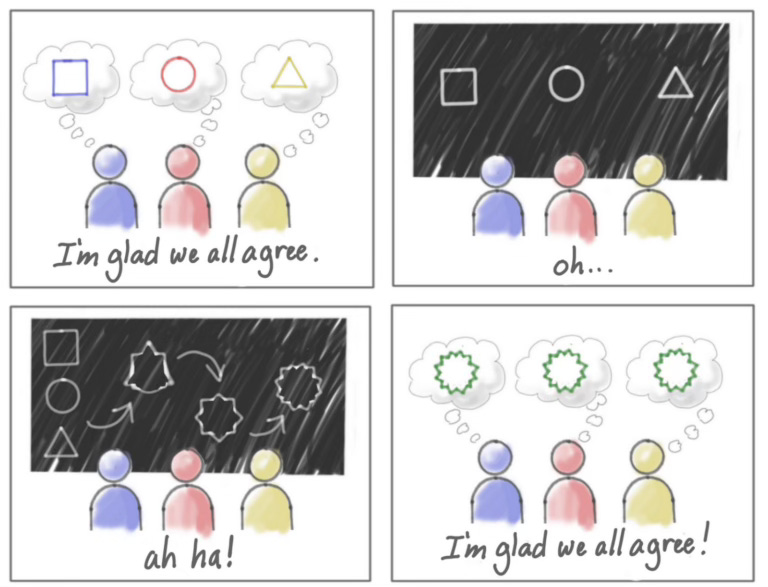

Why shared language doesn’t always mean shared understanding — especially in change.

You say tomato, I say tomato

Change isn’t one thing. It’s many. And the trouble is, we rarely say which kind we’re talking about.

In their book Spiral Dynamics, Beck and Cowan (2005) offer a helpful distinction that’s stuck with me for years. It’s one of the few frameworks I come back to, again and again, in my work with change leaders. Their insight? That there are multiple variations of change—each with its own texture, pace, and impact.

This idea echoes a concept from Alfred Korzybski, a lesser-known but influential thinker who proposed a deceptively simple fix for fuzzy conversations: indexing. In short, instead of talking about “change” like it’s a single thing, we should add a small number beside it—Change1, Change2, and so on—to make clearer what kind of change we mean.

In this piece, I’ve adapted and built on that idea to surface eight Change Variations I’ve seen most often in real-world transformations. You’ll find them reproduced below below for easy reference, and I’ll be referring to this in future articles.

Change variation one, CV1

Involves: Fine-tuning.

Example: Think of an aeroplane pilot adjusting the flaps or a slight trim of the wings. We don't need a massive change strategy or hire a change manager. What we need to do is fine-tune the system itself.

Change deliverable: adjustment or update.

Change variation two, CV2

Involves: Reshuffling the deck.

Example: Think of a team; we have ten employees in the same jobs, and we rotate them. We've changed the players, but the system stays the same. The work practices remain unchanged, yet we've refreshed things but not redesigned them. We've moved beyond fine-tuning to a deeper level of change.

Change deliverable: swap-out or increment.

Change variation three, CV3

Involves: The new and improved.

Example: Like a new version of an app or operating system. We're staying within the same operations but with new and improved technology or ways to get things done without a massive reorganisation. It's a modified version of change.

Change deliverable: iteration or release.

Change variation four, CV4

Involves: Hunker-down.

Example: Often indicative of a crisis, this message is it's time to watch the costs and not invest because we must conserve what we have. The organisation may ask people to return to basics and focus on the core business. In their lifestyles, people will have begun to spend less money and pay more attention to the quality of what they have. They will fix the house rather than try to buy a new one because they sense their environment is uncertain and requires a lean mindset.

Change deliverable: simplification or optimisation.

Change variation five, CV5

Involves: Stretch up.

Example: In contrast to the hunker-down, we ask people to begin to behave in more complex ways - in new ways - which are not yet part of their standard operating system. Often referred to as thinking outside the box, we need to be mindful that elements in the box must be preserved. I've frequently found a natural ebb and flow between change variations four (CV4) and five (CV5), as the organisation naturally oscillates between periods of investment for expansion followed by consolidation and integration.

Change deliverable: expansion or optionality.

Change variation six, CV6

Involves: Revolutionary attack on barriers.

Example: Sometimes, this means the leadership has to fire or replace an entire operating unit. It's like a coach has to replace some players because the team's chemistry is sour, as there is a clear need for fresh blood. Sometimes, this is an action that must be taken, so let's not call it radical because it isn't; it's pretty standard because of the nature of the systems and their integrity.

Change deliverable: managed revolution or restructure.

Change variation seven, CV7

Involves: Level up.

Example: Here, we find most transformation work where we change the form from one system to the next.

Many people who live a life of materialism suddenly find that the world is no longer satisfying, asking themselves, 'is that all there is to life?' We will notice a quest for internal peace or purpose as illustrated in "The Graduate" with Dustin Hoffman. In this, we saw a young man struggling with encouragement from his elders to go into plastics but realises there's something interior to him, some urge or something not being addressed. Many people experience a religious conversion, whilst others suddenly are released from dogma and the judgements of shoulds and oughts as the autonomous person begins to flower like a butterfly.

Others may join a retreat centre, meditate, or practice yoga searching for spiritual truths, even to the point of walking away from a lifestyle and family because of the urge to transform into something different. Tread carefully here as CV7 is so powerful in the heart and soul. It is the realm of purpose and integrity.

Change deliverable: managed evolution or transformation.

Change variation eight, CV8

Involves: Epic change.

Example: Typically reserved for times when significant shifts across multiple domains produce epic changes like the industrial age, the information age, and now the age of molecular biology and artificial intelligence. These are daunting and very threatening to people because so much is happening quickly in many areas. It often induces fear and uncertainty, creating stress in the system because we still need the capacity to provide clarity and precision to inform people to change from what to what. In these situations, we're much better off if we can involve people in designing, without certainty or guarantees, the transition from what to what and how.

Change deliverable: managed disruption

First and second order change

According to research (Levy, 1986), a system can change in one of two ways:

First order change (CV1-5) - “It consists of those minor improvements and adjustments that do not change the system’s core and that occur as the system naturally grows and develops”.

Second-order change (CV6-8) - This creates a new way of seeing things entirely and requires new learning involving a nonlinear progression as the system transforms from one state to another. The aim would be to enable the individual and collective to behave, think, or feel differently.

So, we see that when considering organisational change, it is essential to understand the type of change we're undertaking to know how to support the system. I'll write more on this when we consider how to change and the industry's best practices for change.

Let’s open it up:

Which of these change variations have you seen in your work?

Have you ever assumed agreement, only to find you were talking about very different kinds of change?

What helps you bring clarity when conversations get murky?

✨ Share your thoughts below — or bring a new variation of your own into the mix.

Credits

A big thanks to Jeff Patton, for your comic genius.

Resources

Beck, P. D. E., & Cowan, C. C. (2005). Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership and Change (1st edition). Wiley-Blackwell.

Korzybski, A. (1994). Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics Fifth Edition. Institute of General Semantics (27 Oct. 2023). https://amzn.eu/d/duQwprU](https://amzn.eu/d/duQwprU

Levy, A. (1986). Second-order planned change: Definition and conceptualization. Organizational Dynamics, 15(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(86)90022-7